The Calder witch hunt of 1643 to 1645 saw at least five women accused and executed as witches, and 85 years later the Kirk of Calder was embroiled again. The 1720 Calder witch hunt became a notorious Scottish cause-celebre, written about by literary giant Sir Walter Scott.

It all began with 12 year old Patrick Sandilands, the 3rd son of Lord Torphichen, at the centre of some very odd incidents. The boy was thrown around his bedroom at Calder House; told his sisters {Grizel, Christian and Wilhelmina} about things happening to people out of his sight; passed black urine; and on one spectacular occasion his governor witnessed a bright flash at the bedroom window as Patrick lay sleeping, followed by another a few minutes later. The boy then woke and told his teacher he had been to Torryburn, a village 15 miles away in Fife.

The Sandilands family were upset, the most obvious explanation was witchcraft and Patrick’s father soon suspected an elderly local woman of bewitching his son. She was apprehended, and on the 13th of January 1720 Reverend John Lookup, minister at Calder parish, reported to the brethren of the Presbytery at Linlithgow that:

‘For some time bygone a most respectable family in his parish had been infested with witchcraft; that Mr P, their son, has been sadly tormented and that already a woman has confessed her sin of witchcraft and that she has been active in tormenting the said child’. (McCall, p236)

The woman {we don’t know her name} was said to have confessed to bewitching Patrick Sandilands, and other acts of witchcraft. One harrowing accusation centred around the death of her child many years before. Evidence apparently came from a grave digger who believed there were only clouts {cloths} and no body in the baby’s coffin. Despite explaining that her baby had been very sick and was so tiny when they died that it must have looked like just cloths in the coffin, she wasn’t believed and later confessed to giving the baby’s body to the Devil to roast.

While imprisoned the woman would have been harshly treated; likely dressed in sackcloth, chained in stocks, and kept freezing cold with little food. Beatings and sleep deprivation were commonly used to extract confessions. Under this duress she went on to implicate two other women and a man and they too were apprehended and accused of witchcraft.

Although prosecutions for witchcraft were far less common by the 1720s, people retained a strong belief in witchcraft and the power the Devil held over those accused of being witches. The Sandilands family and the minister were keen to prosecute the people they had accused but the Crown counsel refused to proceed with a legal case against them. This left the church with a problem: how to resolve the case to the satisfaction of the ‘most respectable’ (financially benevolent and therefore highly influential) Sandilands family, who clearly believed the Devil had visited them.

Linlithgow Presbytery decided that a sermon and congregational fast were the best solution.

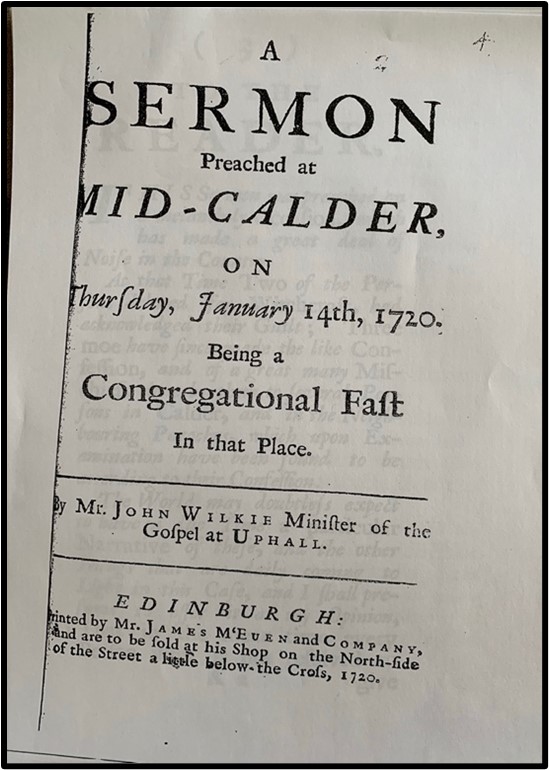

On the morning of January 14th 1720 the parishioners of Calder were ordered to fast, and congregate at Kirk of Calder where the Reverend John Wilkie from nearby Uphall parish preached a long, vitriolic sermon. The four accused people, local parishioners, ministers from neighbouring parishes and the Brethern were all present.

The sermon was over 30 pages long and Rev Wilkie did not hold back, giving dire warning to those who might consider being in the service of the Devil:

“Do you know what you have done? You have exposed yourselves to the Wrath of God, to that Wrath the Power whereof no man knows, before which no Creature is able to stand; to that Wrath before which the Mountains quake, and the Hills melt, the Earth is burnt up, and the World and all that dwell therein; to that Wrath which is powered forth like Fire, and by which the Rocks are thrown down: To a more exquisite Torment, than a Lake of Fire and Brimstone could cause to a living and most sensible body, this throughout endless Eternity; To the gnawing of the Worm of Conscience that will never die, or intermit it's untolerable Gnawings.”

Lord Torphichen arranged for the sermon to be published by Edinburgh printer James McEuen who sold copies ‘at his shop on the North-side of the street a little below the cross’.

Events at Calder also caught the attention of the notorious ‘Tinklarian Doctor Mitchell’ who wrote a brilliantly titled newsletter “Doctor Mitchell’s strange and wonderful discourse on the witches and warlock of West Calder”. This describes him walking eight miles to Calder while fasting, speaking with Lord Torphichen’s staff (who were eating, drinking and ignoring the fast), and then to Lord Torphichen himself. Dr Mitchell also spoke to two of the accused, a man and woman who he describes as husband and wife. They were said to have confirmed their allegiance with the Devil.

This publicity led to long lasting and widespread notoriety; Sir Walter Scott writing about the case in his 1830 ‘Letters of Demonology and Witchcraft’ and Hardy Bertram McCall noting in 1894 that:

“The ‘Calder witches’ were at one time as proverbial in this country as the Lancashire witches in England”

There’s some speculation that Patrick Sandilands could have been ill, suffering from seizures or delirium, although it is more widely accepted that the boy was up to mischief, possibly in cahoots with his tutor. His family seem to have become embarrassed by the whole episode and they later sent him off to sea. Patrick went on to captain an East Indian Company ship and perished in a storm far from home.

The case is written about as foolishness and often looked back on with humour, but the people who were accused of witchcraft suffered greatly. There are different accounts of what happened to them but at least two, possibly all of them, died not long after the January 1720 sermon. Their harsh treatment during a cold Scottish winter no doubt contributing to, if not causing, their deaths.

The names of the people who suffered have been lost through time, although secondary sources give one of the women’s names as Ellen Fogo. Ellen’s husband, John Dunipace, was a pauper whose poor payments ended in January 1720. This may have been because he was the husband of a suspected witch, or perhaps he was also accused and Ellen and John were the wife and husband Doctor Mitchell spoke to.

Sources

- McCall, H, B. (1894) The history and antiquities of the parish of Mid-Calder, with some account of the religious house of Torphichen, founded upon record. British Library.

- Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft, Addressed to J.G. Lockhart, Esq. By Sir Walter Scott, bart. London: John Murray, Albemarle Street. MDCCCXXX.

- A sermon preached at Mid-Calder on Thursday, January 14th 1720. Being a congregational fast in that place. By Mr John Wilkie minister of the gospel at Uphall. Edinburgh. Printed by Mr James McEuen and Company.

- Doctor Mitchel’s strange and wonderful discourse, concerning the witches and warlocks in West Calder. William Mitchell. Electronic resource. National library of Australia.

- Sinclair, G. (1685/1864) Satan’s Invisible World Discovered.

- Chambers, R. (1858) Domestic annals of Scotland v. 3. Chambers, Edinburgh.