The Scottish Witchcraft Act of 1563 condemned to death those convicted of witchcraft. Across Scotland the act led to at least 4000 people being formally accused of crimes that we now know are ridiculous and impossible. At least 2500 people, mainly women, were executed 1.

The “Calder Witches” were at one time as proverbial in this country as the Lancashire witches in England 2

The first mention of witchcraft associated with Calder parish came in the late 1500s. The minister at the time was Rev John Spottiswoode an important Scottish religious figure who later became Archbishop of St Andrews. Spottiswoode wrote that in 1590-91 he had spent ‘most of this winter in the discovery and examination of witches and sorcerers’ 2. Rev Spottiswoode was most likely referring to his work with national commissions to try witches across Scotland as there are no apparent records of people in Calder being accused of witchcraft around that time.

There was also a single well known case in the parish in 1720 when a young member of the wealthy Sandilands family was said to have become possessed, leading to several older local women being accused of witchcraft. Some of the women died while imprisoned and others were subjected to cruel treatment followed by a humiliating public sermon by the minister. The incident was so notorious that Sir Walter Scott wrote about it in 1830 3.

However, the most prolific period of witchcraft accusations at Calder happened between 1643 and 1645. In April of 1643 Hew Kennedie, a 22 year old graduate of St Andrews University, was appointed minister at Calder. Almost as soon as he was ordained Kennedie, along with local nobleman Sir William Sandilands and kirk bailie James Sandilands, began a ferocious mission to eradicate witchcraft from Calder parish. Over the next two years ordinary parishioners were imprisoned, tortured, and executed as witches. All the accused people at Calder were women and the witch hunt crossed local boundaries to involve others from nearby parishes, most notably South Leith and Carnwath. In 1644 at least five women from Calder were executed: worrit ‘strangled’ and burned at the stake.

The names of the women who we know were executed are Agnes Bischope, Agnes Vassie, Marioun Gibsone, Jonet Bruce, and Helen Stewart.

Margret Thomson, Margaret {Marion} Ramsay, Isobel Ewart, Jeanne Anderson, and Bessie Stevinsoun were also accused or personally affected by accusations, and it’s likely that were others, possibly many others, whose names are now lost to us.

Calder Parish

In the mid 17th century Calder was a parish, a large rural area known as Calder Comitis that included the villages now called West Calder and Mid Calder. Although geographically large it had a relatively small population, probably of about 1000 people. Situated around 15 miles from central Edinburgh, the area was an important stopping point for drovers headed north and south with their cattle, and for covenantors seeking shelter with allies. The area’s proximity to Edinburgh made the parish important politically and ecclesiastically: John Knox is known to have spent time at Calder and often preached there; and at least two Calder parish ministers, including Hew Kennedie, went on to become Moderators of the General Assembly -heads of the Church of Scotland.

In 1643 the parish had two churches: the long-established Kirk of Calder at Mid Calder, and the new West Kirk at West Calder, built that year. Until 1647 both were overseen by the Calder kirk session. The kirk session was led by the minister, supported by the kirk bailie and church elders, and oversaw local administration such as payments to the poor and appointing school masters. The session was also the first tier of the Scottish legal system and it was usually the kirk session who acted upon suspicions of witchcraft: first they accused a person and gathered preliminary evidence, then went to the local presbytery at Linlithgow to request permission to hold a trial, finally seeking a commission and verification of guilty verdict from the Privy Council of Scotland at Edinburgh.

The people affected

The people who were accused of witchcraft were not witches, they were ordinary Christian folk. At Calder some were singled out for persecution because they were considered a nuisance to the kirk or had argued with their neighbours, others simply had the bad luck of being related to or known by other accused people. A few appear to have been traditional folk healers and midwives providing the only health care most people could access.

We have found links between the women accused of witchcraft at Calder and those who were accused at South Leith and Carnwath parishes at the same time. The women may have known each other or been related, but it’s also clear that ministers colluded across parish boundaries to drive accusations. So far, we know the names of 24 people who may have suffered because of witchcraft accusations at Calder, with more only referred to as ‘certain witches’ or ‘burned witches’. At least nine of the 24 were executed, and it is highly likely that others were also executed. The diagram below illustrates the links between the people accused of witchcraft at Calder, Carnwath, and South Leith parishes.

As the project progresses we hope to find out more about the people affected and involved, the links between them and what their lives were like.

Our project

The stories from this time are fascinating, they include forced confessions of encounters with the Devil, shape shifting, and flying on cats and trees. There are accounts of cruel treatment and horrific punishment, but also escape from prison and standing up to those abusing their power. The places where this happened remain familiar: the Calder kirks with their stocks and jouggs and penitent stools; witches’ meetings on Levenseat and Tormywheel hills; people living at Nether Williamston, Corston, Dedridge, Pumpherston, Easter and Wester Yardhouses, and Muirhousedykes (now Loganlea near Addiewell); and finally Witches Knowe at West Calder and Cunnigar Hill at Mid Calder where women were executed and their bodies burned.

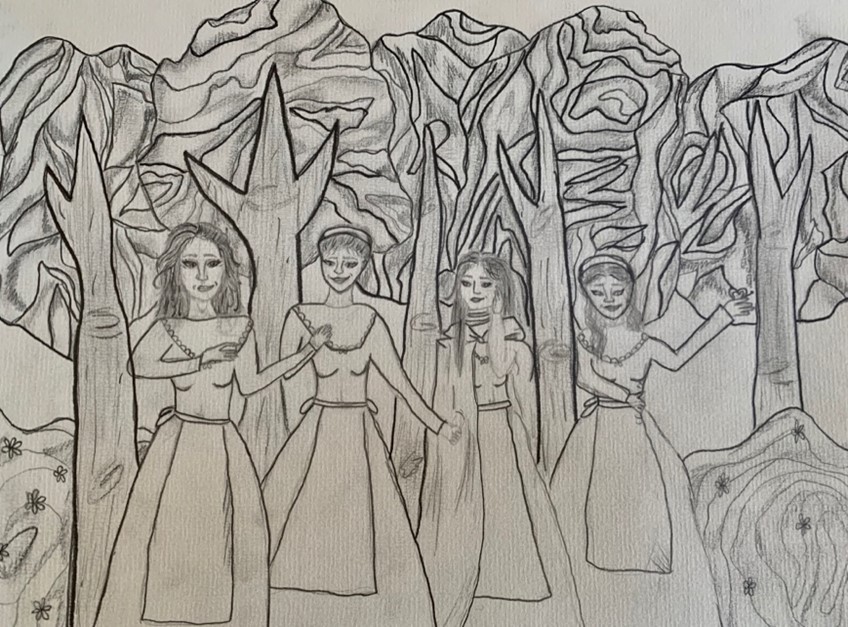

One of the main aims of our project is to find out more about what happened. We are currently transcribing old documents that refer to the witchcraft accusations and building a website that will tell this part of our local history. The project will also include artwork, photography, video, poetry, a play, and pop-up exhibitions. We hope to tell the stories in factual, sensitive, and interesting ways, building a strong source of information about what happened while remembering and commemorating the women who were affected.

The Calder witch hunt was intense but relatively short lived, starting in late 1643 and coming to a halt in early 1645. Apart from the sole 1720 case there are no further records of witchcraft in the parish beyond April 1645. The minister and bailie appear to have been challenged at least twice about their conduct through appeals to Linlithgow Presbytery by Issobel Ewart and her husband Sir William Douglas, and to the Privy Council by Margaret Thomsone and her husband Alexander Gray 4. It may be that Kennedie, the Sandilands, and the kirk elders came under pressure to stop hunting witches and lost the support of the wider community. It’s also of note that around the same time that the accusations stop the Calder and South Leith kirk session minutes become preoccupied with dealing with plague and pestilence: orders prevent strangers from entering kirks, rebuke those who refuse to stay at home, support the bereaved, and provide charity to people who have no income.

...numerous entries {of the Calder kirk session} at the same time restraining all communication with Edinburgh, “in regard the pestilence is so frequent yrin {therein}”, and forbidding any of the parishoners to entertain strangers in their houses. For offending against the latter… Andrew Oswald of Lethame, John Muirheid of Lynhous, James Tenent of Overwilliamstoun and Andrew Lockhart of Braidschaw were rebuked by the session. 2

The now familiar requirement to divert time and resources to address the effects of a pandemic may have helped end the Calder witch hunt. We hope that our research will shed more light on this and the many other questions we have about what happened at the time.

References

- Goodare, J, Martin, L, Miller, J, Yeoman, L. The survey of Scottish witchcraft. www.shca.ed.ac.uk/witches (archived January 2003) Accessed February 2022

- McCall, H, B. (1894) The history and antiquities of the parish of Mid-Calder, with some account of the religious house of Torphichen, founded upon record. British Library.

- Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft, Addressed to J.G. Lockhart, Esq. By Sir Walter Scott, bart. London: John Murray, Albemarle Street. MDCCCXXX.

- Register of the Privy Council of Scotland. Ser 2 v8 1644-1660 At: babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015073339486&view=1up&seq=127&skin=2021&q1=calder Accessed February 2022